Excerpt

Download a PDF of this excerpt from the first chapter, or read it below. You can purchase The Belle of Two Arbors online, and where all fine books are sold.

WINTER 1913: GLEN ARBOR

The gentle rise and fall of the ice under our shanty didn’t bother. The slosh of water from the fishing hole, washing my little brother’s bobber over the boots he’d taken off, did. At the sight of the long pier in front of Bell Stove Works trembling, my frail Mama dropped her line and raised her gray-gloved hand to her ear to listen for any warning. There wasn’t any, not even the whistle of the wind. As we waited for worse, the calm deceived. That certain slant of bright winter light now illuminated only a still sheet of ice on the bay and the solid buildings ashore. The black stove beside us stood sturdy and warm on the thick ice. Pip dropped his bobber back through the hole into the water, and Mama picked up her line. We waited for a mess of perch to bite.

▪︎ ▪︎ ▪︎

After a four-day blizzard had cooped us all up and ruined my hope of a big party on New Year’s Eve for my 14th birthday, January 3 had broken clear and mild. Papa left before dawn to join his men at the factory overlooking Sleeping Bear Bay. No dumb yes-man foreman, my father, Paul Peebles. He had the smarts, and ambition, to marry my Mama, Mary Bell, while she was still fertile despite her then 39 years. Papa soon took over running the stove works her father, Ian Bell, had founded in Glen Arbor.

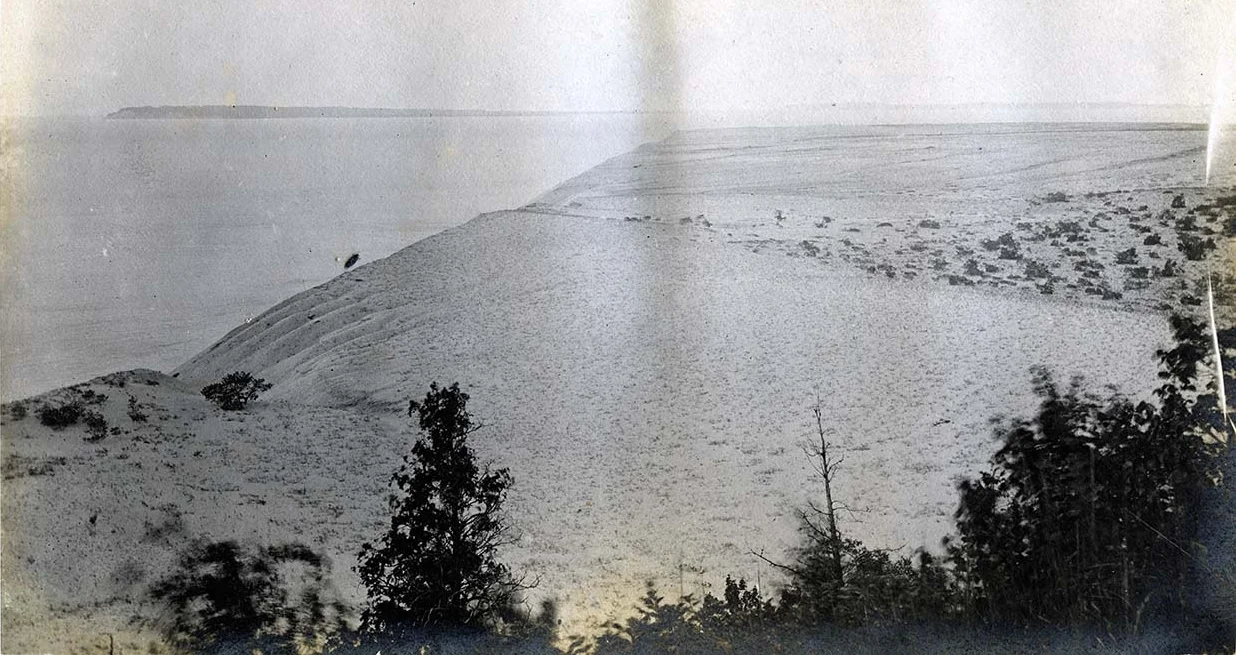

Grampa also built our house as part of her dowry, along with a mile of lakeshore and dunes, woods, meadows, and steep hills. All in all, he’d bought more than a thousand acres on either side of the Crystal River from the first white settlers in these parts.

I rose in the dark house to prepare breakfast for Mama and my six-year-old brother. I mixed up the eggs, flour, baking powder, milk, sugar, and melted butter and poured the batter on the griddle-top, dusted the pancakes with powdered sugar, stacked them on the plates, and put the syrup from our big maples on the table. While Mama pecked at a single serving, my little brother ate three helpings and asked for more. I never could say no to him, even if his late, long birth nearly killed dear Mama, and she’d never been the same since. She’d lost an inch a year thereafter as her back stooped, her legs whittled to sticks, and she fell into a wheelchair. Pip wasn’t to blame: What was my father thinking, getting Mama pregnant at 46, anyway? I knew: Papa wanted to sire a boy to take over the Bell Stove Works and continue its operation as Peebles and Son. Papa and Mama had the misfortune that they gave birth to me, a girl, first.

It’s odd what we inherit from our parents and what we don’t. Pip got his nickname because Papa named him Paul after himself and gave him a middle name, Ian, to seal the Peebles takeover of the Bell business. There was so much confusion, what with “Paul” and “Ian” ringing back and forth between my Papa and Grampa, that soon we all called our boy “Pip.”

The little guy got his good looks from Mama. His hair was straight and dark as most of hers, his eyes the same pale gray-blue, his bright smile just as irresistible. Mama had a white forelock, about which Papa always started to tell a story to all who would listen. He said it made her a better looker than that beauty queen who’d become such a sensation in those new-fangled moving pictures. Miss Nesbit played the lover in the film—and in real life—of the rake Grampa and Mama hired from New York to design our home. “Thank heavens,” Mama picked up telling the family yarn, “the hussy’s husband had murdered the philandering architect at his Madison Square Roof Garden rather than our front porch”—or Papa would never have stopped regaling all within earshot of the racy tales of Stanford White. Sometimes Mama couldn’t resist adding, her white streak, blue eyes, and bright smile flashing as if a young woman again, “Bell Cottage is the best shingle-style house in the country.”

Mama was fiercely loyal to our home, as she was to my brother and me. Pip, bless him, was just as loyal to Mama and me, even if I couldn’t help feeling a trifle envious he’d no doubt soon sport Mama’s becoming white streak. With my dark red hank of unruly hair that Papa gave me, I didn’t inherit Mama’s striking looks. I also began to chafe at her undying devotion. Maybe as a teenager I wanted to try my new wings to see if I could fly outside by myself, but I shared Mama’s fear of leaving the hearth that sheltered both of us for so long. Already taller than the older boys and gawkier than any of the prettier girls, I tried to hide my embarrassment at my early ripening as best I could at school. But I never got over the other kids whisper-ing and pointing at me as if at a freak. At least at home I had a role, taking care of Mama and our boy. Papa talked once about hiring help, but Mama insisted we needed to invest every penny into the family stove works. My deft touch cooking, cleaning, mending, and minding also earned me Mama’s thanks, even when our skin irritations at being cooped up for several days in a row sometimes made me wish I didn’t have to tend her so.

Oh, there were times I also wished to shut my little brother out when he wasn’t in sight, but I never could resist caring for him when he popped into view. With his cheeks white from the sugar and syrup dripping off his tongue between his missing two front teeth, he begged me to take him “to see the big boys pu’ the s’oves ’ogehew.” He couldn’t yet enunciate his T’s and R’s. I could only nod.

After washing and drying his face, I helped Pip put on his warm leggings, button his winter coat, lace up his boots, and clamp on his red stocking cap. When Mama said she wanted to come along, I was surprised. She hadn’t set foot outside Bell Cottage since our annual rite of delivering turkeys the day before Thanksgiving. At that time we’d first dropped by the homes of the men in Glen Arbor and Port Oneida who worked for Papa at the factory to say thank you. Next, we’d visited the poorer Ojibwe families left in their few remaining but better-kept frame houses in Ahgosatown. Mama said they’d prefer a job at Bell Stove Works, but Papa said it was too far from the east side of the peninsula. Too far to walk or to travel by horse and buggy, yes. “But not to catch a ride in those new Tin Lizzies?” I asked. “Not too far to set up camp next to Glen Haven and work at D. H. Day’s lumber mill or big dock to the west of us,” I pressed. Mama looked sad and shook her head. These men were good enough to convert and serve as deacons in the Omena kirk they founded and kept up; were they not good enough for Papa to hire?

Yet when Mama gave me her best smile, I never said no to her either. So I helped her put on her winter gear, gray gloves, and woolen cap. I steadied her as she hobbled out to her makeshift sleigh, a big sled with a seat and handrails. Pip and I strapped on our snow shoes and pushed Mama up the short lane to Sunset Shore Road. The frozen bay, pure white from two feet of fresh snow, extended west to Sleeping Bear Dunes. Far to the north, only a narrow strip of dark water rippled in the strait to the two Manitou Islands.

As we passed the mouth of the Crystal River, Pip wandered off to chase a rabbit. On his snowshoes his little legs raced across the deep drifts almost as fast. On his skates, he was even faster: Papa called his son “my river skater” because he picked up speed the longer he scooted along. On snow or ice, as on land, I lumbered, big and slow. In the Great Lake, I floated and swam for hours on end, not as quick as a brookie in the river, but as strong and, yes, graceful as a big sturgeon in the lake. Little Pip, so trim and wiry, was a sinker. Maybe his oddly sunken chest didn’t hold enough air. As long as he could wade in the river to fish, dip his toes in the shallows to skip stones, or skate on a frozen surface, he danced with the best. Put him in water over his head, and he was lost.

I pushed Mama until Pip rejoined us at the crossroads of Glen Arbor. He pushed the sleigh the rest of the way on Lake Street to the stove works, only a couple hundred feet from the long pier on the bay. When the little boy popped his head through the backdoor, Papa blocked the way. When Pip tried to step around him, Papa stood his ground. Papa’s brush-cut, dark red hair bristled above, and his plain face, dark eyes, and flat nose couldn’t hide his brute strength. He pushed Pip back. Seeing the crestfallen look of his heir to the family business, Papa turned to me. He directed me to go to the office, get the jigs and bait, and take Pip ice-fishing. Patting his boy on the shoulder, he added, “The stove’s already lit in the shanty for you.”

When Papa turned his back to shut me out, I stuck my foot in the door. When he glared at me, my eyes were now level with his. I stared back until he saw Mama bundled in the sleigh. When Papa gazed more sorrowfully at her, I asked, “Do you think it’s safe for Mama out there?”

“Good God almighty, Martha, the ice’s thick enough to hold a pallet full of our stoves.” He had a business to run, and not enough time to play with his little boy this morning or for his invalid of a wife any day. Those were my jobs, and he’d given me what for the few times I neglected my duties. He turned and shut the door, but I managed to step back before it slammed on my foot. I had learned to stay out of Papa’s way.

I tried to tell Mama we should go home and read poetry to Pip—whether Miss Dickinson or Miss Barrett or his favorite Rabbie Burns—as we’d done so often when Papa was busy, but she turned to the little boy. When he raced toward the office, she looked up from her sleigh and smiled. “Let’s catch a mess of perch for lunch.”

We pushed Mama’s sled atop the snow to the fishing shanty a hundred yards beyond the end of the pier, where the great lake steamers docked eight months a year. Pip and I took off our snowshoes and helped Mama off the sleigh. I opened the door. The big Bell Stove made the shanty so hot inside Mama said we could take off our coats and leggings. She kept her gray gloves on to fiddle with the hooks. When she saw our boots getting soggy from the top layer of the thick ice melting, she took off hers, propped her stocking feet on the asbestos board under the stove and told us to do the same.

I don’t know whether I could have saved Mama if I’d helped her onto her sleigh as soon as our shanty came to rest after the first rise and fall of the ice, when the water sloshing through the fish-hole and the trembling of the big pier stopped.

The sound of the thunderous crack hit us as our ice shanty rose and fell the second time. The ice inside our shanty split in two, silver shards flew all around, and water erupted like a geyser from the fish-hole.

Mama toppled off her stool. Her gray woolen cap followed and floated, in slow motion, through the air until it came to rest on her shoulder. The white shock of hair splitting her dark head pointed through the open door to the dark water spreading between the two jagged sides of the ice splitting toward the pier. Mama pushed Pip out the door as the frame teetered and the studs creaked. The crack widened and then raced to shore as if the frozen bay had been struck by a giant cleaver.

Despite looking so frail sprawled on the ice, Mama pushed—hard—at my shin. I tried to pick her up, but she was too strong. “Save him,” she said. The ice on either side of the widening chasm, inside the shanty and out, began to break up.

I stumbled out the door. I grabbed hold of Pip, turned, and looked back, but Mama only smiled through gritted teeth. As the big stove loomed behind her and began to sink, she didn’t whine. She never had. She waved her gray-gloved hand, the look in her gray-blue eyes already distant, and said so softly I could barely hear, “Take care…” I thought I heard her add, “…of our boy,” but I wasn’t sure and there wasn’t time to ask.

The wood shanty formed a coffin: Mama and the big Bell Stove her father invented and her husband built sank, sputtering and sizzling, into the deep, dark bay.

The most damnable thought flashed through my head: My wish came true, one less person for me to take care of. As Pip began to sink, the frigid water hit me so hard it knocked that ugly notion out of my head before I could drown in guilt. The ice had already broken into chunks bobbing all around us. I had to swim Pip to shore.

I stretched out, rolled on my left side, and held my little brother with my right arm high on my right side. He didn’t struggle or say a word. I kicked my legs and paddled with my free arm already feeling like a block of ice, but at least it served as a rudder. I swam, as best I could in this crabbed sidestroke, diagonally toward shore to get away from the deep channel for the big ships. Surprisingly, on this bright, cloudless day, the water was dark. Opaque with fine sand stirred from the bottom, the bay seemed too heavy to yield to my kick or stroke.

I couldn’t tell how long I tried to swim, but eventually a strange sensation began to creep over me: my body became so numb it seemed to warm. Even my stone-cold left arm came alive, and I began to paddle more strongly. I guess I lost myself swimming in that water, now calm, no slosh, no sound except Pip’s rapid breathing in my ear. No matter the cold or the distance to shore, fear didn’t strike me down. Instead, a sense of exhilaration lifted me up.

I looked over my shoulder at Pip’s face, his dark hair wet—al-ready sprouting ice crystals—his lips blue and smile gone. Fear now clouded his pale blue eyes, usually so clear and deep. “Mawmie, don’ leave me.”

“I won’t, ever.” Even after he learned to enunciate his R’s and T’s, I would always be “Marmie” for him. I hated my first name, Martha, anyway. It always sounded so dour, maybe even unloved when my father said it. But I loved my Grampa and Mama, now both gone, and the family name they gave me as a middle name. I hugged Pip close. “Just hold on, and Marmie will take care of you.” For the rest, even Papa, I vowed I wouldn’t accept being called “Martha” ever again.

My left arm paddling so strong soon scraped the sandy bottom, and I felt the rush of excitement at swimming us to safety. Then the frigid water once again seemed to cool so it must have stunned me. The last thing I remembered, though, was a sense of relief. The great blue water had buoyed us up.

Sometime that evening Papa came to my bedroom on the third floor of the turret. I’d been dreading this moment since I fell into a deep sleep. Occasionally, I had heard one voice or another outside my door say “tremor,” “upheaval,” “quake,” and “out between the islands”—once even a French word that sounded like “seiche”—but I was afraid Papa was angry with me for not saving Mama. Maybe I was just in shock from nearly freezing or too quickly thawing. When I heard Papa’s knock, I bolted upright.

He sat down beside me. “I’m proud of you, Martha.”

“Please, Papa,” I blurted, “don’t call me that anymore.”

He was silent for a long while before he said, “You kept saying that when we dragged you and Pip ashore, all the way to the stove works and the sleigh ride home.”

I couldn’t remember, so I only nodded.

“What would you like to be called?”

“Bell.”

“Your Grampa’s name?”

“The name I also share with Mama.”

I thought his short-cropped red hair bristled again, but he said, “How about we add the letter E on the end, so you can have a proper first name rather than just a last name?”

I was so surprised he didn’t object, I just nodded. No point in arguing with him now about dropping the last name of Peebles I got from him.

He pulled a small package from his pocket and handed it to me. “Your mother and I had planned a proper birthday party for you over supper today, but…” There followed another long silence. “Your Mama was going to give this to you. She said it’s for your eyes only.” He handed me the gift, patted my hand, and turned to go.

“Wait. How’s Pip?”

“You saved him, Marth…, I mean, Belle.”

“What about Mama?”

“If we don’t get buried by another blizzard, Pastor Weir will lead the memorial service Sunday at noon.” He turned to go again.

“But what about Mama?”

“We couldn’t risk trying to recover her body.”

“But she wanted to be buried in the old cemetery behind the Omena kirk.”

He sat down beside me again. I reached out but brushed against him. He must have been as embarrassed as I was by my new awkwardness, because he pushed himself away and said, “Not until all the ice melts…” He dropped his eyes. “I’m sorry, Belle.” He shook his head. “Not until spring.”

After he left, I set the package on my bedside table. I got up and locked the door on him, as he’d locked himself away from me. When I turned, I saw myself in the tall mirror above my bureau. I filled up most of the frame. Almost six feet tall, my shoulders stood square: Mama wouldn’t ever let me slouch to hide my height, but my large frame hid most of my thickness. Underneath my wool gown, though, my two new big mounds, ugly as sin, rose. I wondered what Mama would advise now, given her prior order: “stand tall and throw your shoulders back, even if you aren’t ever going to be a nimble, light-stepper on any dance floor.”

I tried to throw my unruly hank of hair forward to see if that would offer any cover-up. No luck, the wild, dark, red, tangled mass just rode on top of my big chest. I closed my eyes but couldn’t resist reaching up.

I dropped my hands quick, but my face, suddenly flush, still stared back at me from the mirror. A plain face, perhaps: eyes so dark navy they melded into my pupils, nose flat, lips neither a thin grimace nor a fat pucker. Skin not alabaster with the rouge cheeks of a stage star but, thank the Lord, not red freckled either. At least my teeth were straight like Mama’s, not bad for smiling in good times, better for gritting in bad.

I looked deeper into the mirror and saw the reflection of the quarter moon peering through the clouds high in the sky. I turned and walked over to the window. A floor below, Pip hung out his open sash peering through the captain’s telescope he got for Christmas. More than a wanderer on land or a tinkerer in the shop, he was a dreamer gazing deep into the heavens. He looked up. He tried to smile. Finally he lifted his hand. Not a wave, but a call for help. I nodded.

Pip knocked on my door, and I unlocked it. He dragged his telescope behind him and hopped on my bed, his orange-and-white fur-ball of a cat, Mister Stripes, close behind. My brother couldn’t resist the package on the table. He grabbed it but then looked to me for approval. Mama wouldn’t mind if his eyes saw her gift; she never could resist him either. I nodded again, and he tore off the wrapping. He opened the small book, but, when he saw Mama’s writing, he handed it to me as fast as he could. Seeing the green ink and fine scroll of her hand set me back some, too.

The title page read, A Dome of Many-Coloured Glass by Amy Lowell. Between the title and the author, Mama had written, To my birthday girl: May you grow into the best of the new generation of poets. Your Mother, Mary Bell, December 31, 1912.

A few pages into the slim volume, she’d inserted an envelope inscribed in her hand, “For your trousseau.” I read the poem on that page, “A Winter Ride,” to myself. Not appropriate for sharing with Pip this evening: too much joy kiting with the sun on a bright winter’s day. So I flipped through the thin book until I happened on a section called “Verses for Children” and found “The Crescent Moon.” I read it aloud to Pip in hope that it might help him sleep. It started too breezily: “Slipping softly through the sky little horned, happy moon, can you hear me up so high?” After too many more stanzas flying too high, it careered to a point: “I shall fill my lap with roses gathered in the Milky Way, all to carry home to mother. Oh! What will she say!”

Bad enough Pip no longer could carry roses, or anything else, home to Mama. Thankfully Pip didn’t seem to catch this cruel irony, but Miss Lowell’s verse was so thick with sweet honey for me on this bitter day, I almost choked.

So why did Mama give me A Dome of Many-Coloured Glass anyway? I opened the envelope, unfolded her crisp stationery, and read her note:

My Dear Child,

The critics say Miss Lowell will be remembered as one of America’s great poets. But after you read all her images, you’ll know Miss Dickinson’s and your songs sound much better. Don’t ever listen to any teacher, or let any other damn fool, tell you different. Remember your voice always: poetry’s meant to be heard not eyed, so say your lyric aloud!

Love, Mama

I couldn’t help smiling at the memory of Mama scowling at Miss Patterson’s comments in red ink splashed across one of my poems. Whether my teacher assigned an essay, a story, or a report, I always turned in a poem. Mama said, “What’s that pinched-nosed, squinty, four-eyed idjit talking about? ‘Put a capital letter at the beginning and a period at the end.’ ‘Incomplete sentence.’ ‘Too many dashes.’ Hell, damn! You just forget all her scribbles and sing your song aloud to me just as you heard it when you composed it.” When I started to speak, she cupped her hands to her ears as she so often did when she wanted to hear better and said, “Sing it proud, dear!” After I finished, she nodded triumphantly: “You keep right on singing, and I’ll take care of Miss Patterson.”

Through my smile at this memory, I saw that Mama wasn’t here to take care of Miss Patterson—or me—any longer.

Pip tapped my shoulder. “Whewe’s Mama’s body?”

I didn’t know how else to answer so I told him the truth: “Buried under the ice.”

“How’s she gonna get to heaven?”

There was a question without a good answer, but I replied, “We Scots are much practiced at getting lost at sea and finding our way Home.”

“I’m nevew going in deep wawa again.”

So I tried a different answer. I looked out the window. “Maybe her spirit rises separate from her body.” I swallowed hard at that because Mama’s passing tested my belief in the teachings of John Knox that Papa and our kirk drilled into me.

After a long pause to follow my gaze, Pip nodded and tapped his big telescope. “I’ll find hew.” I didn’t know he’d still be searching the stars forty years later, but I hugged him close. My boy would never lose his faith.

After I thought he’d fallen asleep, I turned and placed Mama’s note back in the envelope, the envelope back in the book, the book in the drawer of the bedside table. When I began to turn off t he oil lamp, I heard him say, “Mawmie, leave the light on fo’ Mama.” I turned and held onto our little boy, gritted my teeth, and cried and cried. Mister Stripes climbed between us and purred so I didn’t have to listen to my own sorry thoughts. He lulled me to sleep. Bad enough remembering the scene unfolding; worse feeling guilty over my unbearable flash, thinking I’d only have to care for Pip now when I knew I’d miss my Mama forevermore.

Guilt and Pip’s little cat couldn’t stop me dreaming my Blue Salvation: That feeling of buoyancy while floating in the icy water, of growing warmth as I lost myself swimming, the thrill of fighting to save our boy and me, the burst of joy when my hand first felt the sandy bottom, the cold water stunning, the longer release of making it safely back to shore. This sense of relief enabled me to forget, at least for a while.

Buried beneath the thick down comforters, I got so hot that even sticking one leg out didn’t cool me down. From some place too close by, I heard the sound of the ice cracking and saw Mama and the Bell Stove sinking in their shanty coffin. I woke with a start, thinking I’d never escape that horrible scene. I pushed the covers off both my legs to try to cool off, but not even Mister Stripes’ purring could get me back to sleep.

I stood up, still flushed in my thick nightgown, and I opened the drawer and took out Mama’s gift and note. I looked to make sure Pip was asleep, his orange-and-white fur-ball purring in his ear. Time to go to the secret place Mama shared only with me.

I unlocked my bedroom door, crossed the hall, and entered the attic. At the far end, under a huge quilt Mama had stitched together, stood the big wooden chest next to the floor grates. Inside, for my trousseau, she put books, family pictures, charms, silver, her wedding dress, her dolls, and her jewels in a big lockbox. I sat on the quilt atop the chest and looked north out the window. The moonlight danced across the ice floes thrown on shore and the dark water in the bay already freezing over.

I lost myself dreaming about the thrill of the water buoying me up and the relief of safely making shore. As if in a frenzy, a new song burst forth from my lips:

Your lips are

Blue Salvation—

flowing over my

hills and valleys

cooling the red heat

of my Passion—

soothing summer balm

after the wintry storm—

I replayed the poem in my mind. Not bad for a first try. At least it captured what I felt when the great lake embraced me, even if it missed the rest of what I experienced when that cruel crack took Mama down.

I removed the quilt, opened the chest, pressed the secret lever inside the lid, and took out the key. I gently pushed Mama’s other gifts aside and pulled the locked box from the bottom. Inside were her jewels and a leather-bound book, my Songbook we called it, that she’d given me to write my poems and private thoughts.

I pulled it out and turned to the next open page. I listened harder as I wrote my new song down. I could hear I’d omitted that certain slant of light on this wintry day, the early warning from the initial seiche, the death knell sound of the crack when the ice split, and Mama’s long, gray goodbye as she waved me toward shore. Something else missing nagged, but I was too tired coming down from my rush to figure out what. I inscribed my name and date at the bottom: Belle, January 3, 1913.

▪︎ ▪︎ ▪︎

The funeral in the old kirk in Omena wasn’t as bad as I’d feared. More than a half century earlier, a band of 150 mostly Ojibwe converts built this white clapboard Presbyterian church with the tall steeple, high on the bluff looking south over the frozen Omena Bay on the west branch of Grand Traverse Bay. Today the sky was blue, and the noon light flooded the sanctuary. Even in the absence of a body, guests filled all the pews. I wouldn’t call most mourners, though, as many felt obliged to pay their respects to a member of the Bell Stove clan, one of the few that offered a steady job and a decent wage to folks up north year-round. Then again, most didn’t begrudge Mama her lineage because they remembered her father more kindly than they felt about mine. In fact, Mama, despite her barbs at home, minded her manners enough the few times she ventured out that she didn’t make many enemies. Miss Patterson, on the aisle in the third-row pew on the other side, did give me the eye to let me know I’d have to mind her in school now. Most of the rest seemed a little sorry for my brother and me, even if they thought the end for such a long-suffering soul as Mama some kind of blessing. But what did those ignorant of how much she had shared with Pip and me know anyway?

When I turned to see if Miss Patterson had stopped staring, she looked right past me. From this distance her blue eyes didn’t have to squint over the pince-nez she wore on her pert nose for reading the hymnal. Why, she’d even cut her long hair for the occasion. Rather than scrunched up in an ugly bun that always wanted to fall apart, her short bob, now more pepper than salt, framed a face I barely recognized, not unattractive at all, even becoming. I followed her gaze, turned, and realized her eyes had been fixed on Papa the whole time. Good Lord, what was she thinking? My Mama’s dead body wasn’t even going to be buried in the old cemetery outside the kirk this day.

Our little boy sat fidgeting with his telescope between Papa and me. Papa looked straight ahead the whole time. Occasionally, he touched his son, not to put his arm around him, but to tap him on the back to remind him to sit up straight, like a man. Pip did sit straighter, but he also edged closer to me. When he turned, looked back over his shoulder toward Miss Patterson, and gave his telescope a wave, I feared he might already have deserted to her camp. As I turned to scowl at her, I was relieved to see his older friend and mentor, David, the great-grandson of Chief Ahgosa, waving back at Pip from his seat in the back with the rest of his dwindling band, less than fifty now. Pip always had a knack for joining to play with the underdog, whereas I avoided all the boys and girls, always gawking at me so. I had retreated with Mama to the haven of our Bell Cottage, to care for each other and our boy and to share poetry. Without Mama, where could I escape now?

At least the hymns sped right along, more harmony than dirge. A few times they reached a crescendo when David’s father let loose his deep bass: not even the patch covering the Deacon’s right eye could block his Alleluias from lifting our memories of Mama and reverberating through the rafters all the way up the steeple. Like all his kin, David used the last name of Ahgosa rather than the Scots surname, Potts, awarded at his baptism in the Presbyterian kirk. Like his for-bears, David’s voice still sang to other Gods our kirk would never accept, but the native legends David shared about our Great Lake made more sense to me than the Bible stories from soil so far away.

Pastor Weir spared us singing Rabbie Burns’ Auld Lang Syne or Scots Wha Hae, so the congregation didn’t have to start wailing. He also spared us a sermon about a woman who set foot in this kirk only because her father and husband demanded that their offspring b e raised in all the fire, brimstone, and guilt of John Knox. Instead he gave his strong voice to solo two poems of Miss Dickinson he knew my mother loved. With his sympathetic face, freckled over pale skin, red hair blond from graying, and upper left front tooth turning as if a snaggle, he abridged the first, but in a soft voice to make us all listen harder:

There’s a certain slant of light,

On winter afternoons

That oppresses like the

weight Of cathedral tunes.

. . .

When it comes, the landscape listens,

Shadows hold their breath;

When it goes, ‘tis like the distance

On the look of death.

On this winter afternoon, the certain slant of light through the windows of the old kirk reminded me of Mama’s distant look of death as she pushed me out of the fishing shanty to save Pip. Now, I hugged him all the closer: wherever Mama might be, I wanted her to know I’d make sure she hadn’t died in vain for our boy.

Parson Weir boomed loud the second to close the service:

On this wondrous sea,

Sailing silently,

Ho! pilot, ho!

Knowest thou the shore

Where no breakers roar,

Where the storm is o’er?

In the silent west

Many sails at rest,

Their anchors fast;

Thither I pilot thee, —

Land, ho! Eternity!

Ashore at last!

Oh, how I wished I believed what I’d told Pip—that any God, John Knox’s or any other, could raise Mama’s spirit from the deep to heaven for eternity. Unless she talked with me again, I would only see her buried in the Great Lake.

At least Mama would have been pleased that Parson Weir knew how to pause for a breath on a dash with Miss Dickinson and to sing out her exclamation points. Both sound better when sung right aloud than when read wrong silently on the page. Oh, how I hoped for Mama’s sake my songs could also put Miss Patterson to shame.

The next evening Papa called me to his study on the first floor of the turret. He introduced me to Mr. Robb, “the company lawyer,” who’d driven over from Suttons Bay. Mr. Robb’s short stature, long white hair, and muttonchops contrasted with Papa’s height and close-cropped, dark red hair. The lawyer explained he wanted “to share a problem that you can help us solve.” Mama had executed a will that gave me her half of the shares in the Bell Stove Works my grandfather had left her, and she’d appointed Miss Schultz my guardian to protect my interests if any dispute should arise with Papa.

I remembered Mama taking me to Northport to visit Miss Schultz last year. Mama introduced her as “the only woman lawyer and the only lawyer for women in all of Leelanau County.” So I turned to Papa and asked, “Do we have a dispute?”

“I hope not,” he said. He leaned toward me earnestly. “We’re busting at the seams in Glen Arbor, and I want to move to Empire.”

“Move from here?” I demanded.

“Marth—” Papa started to shout at me but then paused to gain control of himself. “Sorry, I mean Belle,” he said more softly. “The lumber company’s vacating their buildings. It’s my best chance to expand the factory.”

“No, Papa, I mean from here, Bell Cottage, the home that Grampa built for us.”

“Aw, no,” he replied, “we’re still going to live here.” I made the mistake of letting down my guard. After a short pause, Papa continued, “I’ll even buy you a car so you can bring our boy over to tinker with the stoves in Empire any time he wants.” His throwing in a car couldn’t salve the insult to me, now his 50 percent shareholder in the company he married into. “I’m also going to change the name to the Peebles Stove Works.”

I don’t doubt my hank of dark red hair lit up at that, but I took my time to compose my reply. “Papa, we do have a dispute now.” When his face reddened into a beet, I turned to Mr. Robb and said as plainly as I dared, “Nobody’s ever heard of a Peebles stove, but if Papa wants to change the name from Bell, then Empire does have a nice ring to it, leastways if Papa really means to grow the family stove business.” With my best smile I added, “Sorry, I mean Papa’s business.”

Even Mr. Robb’s beady eyes brightened, and he couldn’t help his grin stretching to his muttonchops. “You ever thought about arguing before a jury, Miss Belle?”

I didn’t doubt I’d still need to consult Miss Schultz down the line, but I only answered, “Doesn’t appear we’ll have to this time.”

Mr. Robb nodded and said his goodbyes. After he left, Papa asked, “What would you think if someone came to live with us and helped you with Pip and the chores?”

I thought about blurting that Miss Patterson wasn’t welcome in Mama’s house. Instead I answered, “Thank you, but I can manage.”

When he didn’t argue, I excused myself and shut the door behind me.

I also shut my bedroom door and locked it every night thereafter on Papa. Pip was always welcome. Even on evenings when I was sick of having to mother him all day, I opened the door when he knocked. I’d promised Mama: Pip was now Marmie’s boy.